“You’re not an explorer or an adventurer, you’re just a bookworm,” I told myself. “You dream about venturing off on some tall ship or paddling in Greenland or the Great Bear Rainforest, but you’ll never do it.”

It’s true, I enjoy reading accounts of those who put aside their fears and inhibitions to venture out and discover the unknown. Explorers like Shackleton, Amundsen, Cook, Magellan, Peary, Lewis, and Clarke. How did they do it? Did they bury their fears, or just learn to control them? The Stoics, those ancient philosophers including Marcus Aurelius, Epictetus, and Seneca, had something to say about fear. It was in their four tenets: wisdom, justice, moderation, and courage. They said, focus on what you can control—your thoughts, beliefs, and actions. In a recent blog, Susan Conrad suggests compartmentalizing your fears. “How the heck do I do that?” I wondered.

The Great Bear Rainforest has always intrigued me. I’m attracted to its ruggedness and isolation. I had often mused about venturing into these waters by kayak, but life kept getting in the way. Maybe it was fear that I imposed on myself. Fear of the unknown or what could happen. Certainly, it was beyond my skill level as a novice kayaker. But I wasn’t getting any younger. I told myself that 2024 would be the year that I finally tackled these fears. I would paddle the Great Bear Rainforest.

I would need a plan. And skills. And a partner. How about a partner with a plan and skills? A beautiful blonde my age. Is that too much to ask?

So I signed up for several courses that began early in the spring of 2024. I learned about safety equipment, weather recording, coastal navigation, and rescue techniques. I practised in all conditions from flat to currents, and surf. I could feel my confidence building. I purchased safety gear and upgraded a few camping items. A post by Ms. Conrad on the BC Marine Trails blog outlined how to write a trip report. What a great idea! I’ll channel my inner Herman Hesse, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, and Mark Twain.

But I still required an experienced partner. Someone familiar with these waters. I wondered if Ms. Conrad was available on short notice.

I wrote to her and told her of my plan. I could sense the enthusiasm in her response. This was her backyard, after all. She called me up on the phone. There was excitement in her voice. “What experience and skills do you have?” she asked. “Have you ever paddled there before?” Finally, she said, “Sounds fantastic!” Then she reminded me that we were low on milk. I told her I’d grab some on my way home. Yes!

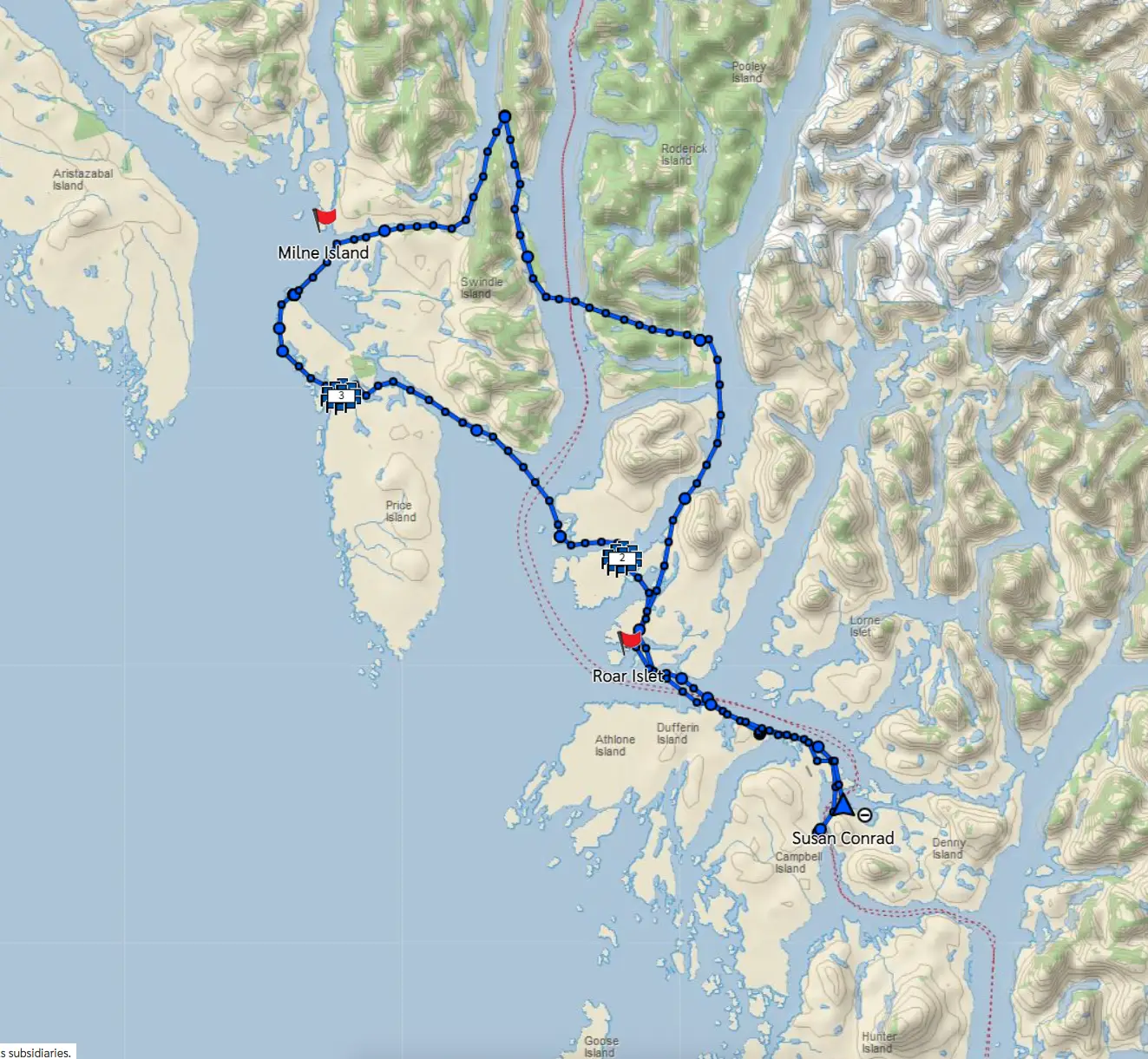

We wrangled two weeks in August for the trip. Susan did all the planning. I did what I could, mostly just what I was told, and tried to avoid getting underfoot. Susan’s plan was to paddle around and between the islands north and west of Bella Bella BC, a distance of about 120 nautical miles. We allowed an extra day in case the weather turned bad, or we just wanted a break. Could I handle paddling all day? Would I discover some new injury? Should something happen to my partner, did I know how to find my way? Could I handle a rescue in rough conditions? Was I getting in over my head?

Before leaving, we photocopied and laminated the route for each day—10 sheets in all. We expected to paddle between 10 and 20 miles per day. We booked our return ferry tickets out of Port Hardy. We marked our charts with several campsite options for each day, should we have to alter our plans. The BC Marine Trails website was a valuable tool in this part of the trip planning. We studied tide and current tables, dried foods, and shopped for the last few items. There was no turning back now.

We arrived late to our bed and breakfast in Port Hardy and departed early the next morning. The attendant at the ferry terminal had said to arrive early to load the kayaks and gear, so as not to cause confusion and inconvenience. We heeded her advice—at least that’s what I noted in my journal for next time.

It was foggy as we departed, but the fog soon lifted, and by the time we arrived in Bella Bella, the day was sunny, clear, and calm. We unloaded the kayaks from the ferry and packed them near the terminal. The exhaustion from the past few days, together with some last-minute shuffling, meant that I did not pay too much attention to where things were packed—an oversight I would come to regret.

Later, we wended our way along the shoreline to our first campsite. It was only eight or nine miles. I felt a bit anxious as we paddled away from the crowd of friends and loved ones who had gathered on the dock to wish us well. Ok, maybe not, but one guy at the terminal did wave to us as we paddled away. Or maybe he was swatting at bugs.

The laminated chart on my deck was buried under my water bottle, sunglasses, bilge pump, and gloves. It was a challenge to decipher landmarks and distances on that first day. The land masses on the chart didn’t jibe with what I was seeing. How far is two miles? It only took a couple of hours to reach our first campsite.

I was tasked with setting up the tent while Susan got the kitchen going. It didn’t take me long to feel frustrated, not knowing where I had packed things. Why was I so anxious? It could be from lack of sleep, or maybe that there was so much to learn. Also, the fact that we were in brown bear country may have played a role. My partner was beginning to question whether this was a sign of things to come.

Eventually, things settled into place and we fell asleep under clear skies. In the morning, we woke to grey and fog. This would be a chance to practice following a compass heading, something I had only recently been taught. Holding a course requires focus, but it was not too difficult. We succeeded in crossing the small channel and followed the shoreline after that. This allowed me to practice my chart-reading skills. I began to feel confident estimating how far away landmarks were in relation to what appeared on the chart. After paddling 16 miles, we arrived at the next campground. I was tired but felt fine. I had been taught to paddle using the muscles in my torso—not my arms—and to rotate my body. The courses were beginning to pay off.

Day three involved the largest crossing of the trip. Five miles across a channel exposed to the open ocean. I had been apprehensive but would deal with the situation when it presented itself. Would the conditions exceed my skill level? Would we get separated? Or worse, lost? Time to compartmentalize—deal with things I could control. We planned to get an early start before the winds had a chance to pick up. In my head, I went through all the self and assisted rescues that I had practised in the spring. Emergency gear, water, navigation equipment, and safety gear were all accounted for and in their designated locations. I had done what I could. The forecast called for calm weather. Susan insisted that we put the miles behind us, as she knew that the wind could build suddenly. Luckily, the forecast was accurate. The seas remained calm for the crossing of just over an hour, but I still found it unnerving.

Meals were always something to look forward to. I especially liked lunches. I was used to a snack bar and maybe some trail mix. Susan knew the benefit of eating well and the impact that could have on our spirits. Her creations were something you were more likely to find in a fine restaurant. We delighted in smoked salmon and oysters, mussels, sardines, and a fine selection of cheeses atop crunchy crackers. We toasted the day with canned wine. Which is pretty good, believe it or not. Life was good—until we ran out of wine.

On the fourth day, we set out into the exposed waters of Laredo Sound. It was lumpy in the afternoon, but nothing we couldn’t handle. The wind died that evening as we picked our way between rocks and kelp beds close to shore. If it had been windier, we would have been forced to paddle much further out, or chosen a closer campsite. We decided to push on late into the evening, as the forecast was for rain and wind for the next two days. This turned out to be our longest day, at 25 miles. Our bodies were holding up, but a rest would be welcome.

The forecast was accurate once again, and we hunkered down for the next two days. We wrote in our journals, sorted through photos, filled water bladders from the tarp, and generally found ways to act silly and keep entertained. By this time, I was getting used to the routines, and, for the most part, could keep track of where I had packed things. I had a chance to listen to and record the weather reports on the VHF radio. This was another important skill that I needed to practise. We examined the charts and talked over plans for the next few days. We were becoming a team, or so I told myself.

“Put it into high gear!” came her cry as we crossed a small channel on day seven. What on earth for? I asked myself. There’s nobody around for miles. But I obeyed, thinking it best not to question her. She had experienced it all in her 5,000 or so miles of kayaking. “Do you see that?” she asked a few minutes later. I peered down the channel at the speck in the distance. “Looks to be a ship of some kind.” It turned out that we were crossing a channel on the path of a BC Ferry. “Paddle faster!” she said. By this time, both of us were doing some math in our heads. If we’re going in this direction at this speed for this long, and the ferry at the end of the channel is travelling at that speed towards us for that long, then…we’re both going to end up…in the same spot! I kept looking over my right shoulder. The angle of the ferry was not changing. I recalled from my course that if the angle of the two vessels is not changing, then the two boats will eventually collide. Collision regulations be damned! Every kayaker knows that might makes right! “Keep paddling,” she ordered. I could tell from her voice that she was uncomfortable with the situation. Ultimately, we did not collide, but gave a sheepish wave to the Captain as the ferry steamed by. But there was a lesson for me that crossings, no matter how innocent they first appear, can develop quickly into a dangerous situation. Sometimes you just have to bite your lip.

On day eight, a gentle wind decided to come from our stern, a breeze of about seven or eight knots. “Perfect sailing conditions,” I thought. As I mused about how nice it would be to hoist a little sail, I thought about the other niceties that were accumulating in the back of my mind. I envied Susan’s whisky hatch for sunscreen, sunglasses, binoculars, and snack bars. And how nice it would be if my laminated charts did not have to be folded to fit on my front deck. And wouldn’t it be nice to put the bilge pump somewhere out of the way, but still within reach. I bet I could find a way to attach a timepiece where I could see it. And how about a small recess in the deck for my grease pencil to fit into? I could jot down little details like high tides and crossing distances. It was a good way to while away the hours.

That evening, as we lay in bed, three humpback whales swam past the entrance of our bay only to circle and come back. This repeated for some time. How wonderful it was to be serenaded to sleep by the sound of whales. We were in heaven.

Day nine began as most others. Coffee, breakfast, move the boats, pack the boats, thank the gods, paddle away. We were headed towards the ancestral village of Klemtu when we spotted a lighthouse. In need of a little social contact, we decided to stop by and say hello. While Susan chatted with the lighthouse keeper, his husky dogs decided to visit me. I was about to pat one when he attempted to board my tiny vessel. But for a quick lower brace, I’d have been turtled. With no harm done, we waved our goodbyes and headed towards Klemtu. Was it Susan’s delicious lunch buffet that caught Fido’s attention?

A short while later, I hear Susan yell, “Whales!” “Where?” I asked. “Feeding in the distance.” Could these be the same whales from last night? We stopped and watched as they surfaced, then disappeared and resurfaced several hundred yards closer, in three to four-minute intervals. They were about 200 metres off and heading our way when they dove. We almost expected not to see them again. Suddenly, a circle of large bubbles appeared off our starboard side. Humpbacks often work as a team to encircle their prey in a net of bubbles, allowing one of the whales to gorge. Humpbacks will also blow a curtain of bubbles as part of the mating ritual. The whales were directly below us. Before we knew it, they surfaced not 15 metres from us. As we paddled away, I wondered if the whales considered us part of their buffet.

On day ten, we paddled back to Bella Bella to complete our trip. We had one crossing of about a mile. There was a low fog bank that morning. We listened for boat traffic as we were not far from the town. Conditions were calm and dry. We double-checked our chart and took a bearing, then headed out. The shoreline on the other side was unbroken for miles, but still, it was a good opportunity to practise. I remembered the lesson from a few days ago that all crossings should be taken seriously. We saw several boats fishing in the channel as we headed towards Bella Bella. We chatted a bit, exchanging tales. I wondered what it would be like to catch a salmon from a kayak.

No crowd greeted us on our arrival. No parade of boats welcomed the returning explorers. No reporters or cameramen from the local news channel fought for our attention. Come to think of it, maybe that was a good thing.

Things were as we had left them ten days ago. I don’t think anybody had even noticed we were gone. Any changes that week took place within me. I felt a profound sense of accomplishment and satisfaction. I had finally paddled the Great Bear Rainforest—a wee bit of it, anyway. Susan was glad for a bit of exercise.

Were my fears real or irrational? I think I have a right to call them real! Kayaking can be hazardous. The weather is unpredictable, and the water is cold. Sometimes you are forced to make a decision that pushes your skills to the limit; sometimes beyond. Bears are unpredictable and can be a real threat. An injury from slipping or a misguided axe could have resulted in anything from having to tow the other person, to a total emergency evacuation.

For me, it comes down to having patience. Sit out a weather situation until the group feels alright to continue. Step carefully on or over logs and rocks. Minimize dangers by becoming educated and practising skills. Get the best equipment you can afford. Travel with a group or go on guided tours until you feel confident. We succeeded because of our preparedness. I thank my partner for her patience, and for teaching me some skills to be a safe and competent kayaker. I hold her in the highest esteem.

I am thankful to those who call the Great Bear Rainforest home for sharing it with us. I am grateful to the people and organizations working to protect this ecosystem. Finally, I thank BC Marine Trails for their map that helped us know what to expect at each campsite. Bon appétit!