In July 2024, our group of four set out on an ambitious kayaking adventure along the stunning Central Coast of British Columbia, paddling from Bella Bella to Port Hardy. Along with the breathtaking views, our meticulous preparation and commitment to the journey made for a remarkable experience. This article explores the intricate planning that went into the trip, highlighting the various aspects that ensured their success. Stay tuned for Part 2 – the trip report.

The Genesis of the Trip

The seeds of this adventure were sown early in 2023, when our adventurous friend, Pat, expressed interest in embarking on a series of bucket list kayak trips. Among these were the challenging routes around Cape Scott and the enticing journey from Bella Bella to Port Hardy. Although I had reservations about my paddling skills, the allure of a remote coastal expedition captivated me.

Over the following months, Pat continued to stoke my enthusiasm, especially as I gained experience navigating Class IV waters. His mantra—“The key to paddling Class IV conditions is to avoid paddling in Class IV conditions”—inspired confidence. By late 2023, another paddling enthusiast, Jenna, joined our ranks, and with my husband Eric, the four of us were committed to our summer adventure.

The Importance of Preparation

Given the remote and exposed nature of the Central Coast route, we understood that thorough preparation was essential. None of us had previously paddled this particular stretch of coastline, nor had we embarked on an expedition of such length. We prioritized risk mitigation and contingency planning, fully aware that we would be entirely self-reliant throughout the trip. This was not a journey for the faint of heart.

Travel Logistics

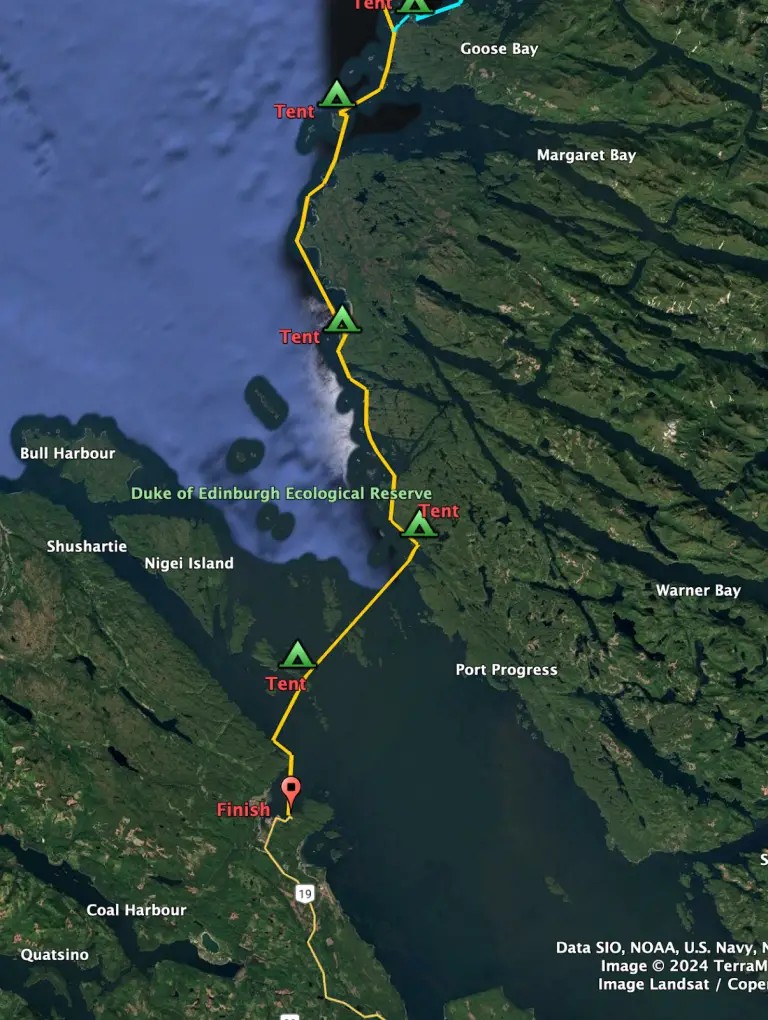

Our adventure began with meticulous logistical planning. We would drive from Victoria to Port Hardy, board the BC Ferry to Bella Bella with our kayaks, and then paddle south back to Port Hardy, where our vehicles would await us. The moment BC Ferries opened bookings for July trips in December, we secured our tickets for July 15, 2024, alongside a hotel reservation in Port Hardy for the night before our ferry ride. With this crucial step completed, the trip preparations truly began.

Route Planning

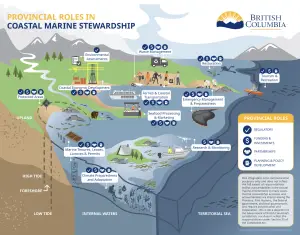

For our route, our priority was to navigate the outside route along the west side of Calvert Island, weather permitting. If conditions were unfavorable, we identified alternative, less exposed routes that would take us safely to Kelp Head, after which the journey would be entirely exposed.

Our estimated paddling distance was a minimum of 200 kilometers, likely more if we meandered about. We estimated ten days of paddling, three days for rest or inclement weather, and an additional buffer day, totaling fourteen days for the entire expedition.

To enhance our knowledge of the route, we scoured every available resource, from books (such as those by John Kimantas), to blogs and articles, as well as the BC Marine Trails map. Our research included discussions with seasoned paddlers familiar with the area, as we sought to pinpoint must-visit tent sites, reliable water sources, and cautionary areas (like Kelp Head and Cape Caution).

The BCMT map was the most useful source for identifying campsites, rest stops, and water sources across the different route options we planned. It was also the tool for measuring distances between sites.

The tools available on the BCMT website for downloading tent sites into CSV format were incredibly helpful to create a list of all possible tent sites on the route (including site details). I condensed it with my notes into a handy printout to carry with me during our journey.

We targeted specific campsites based on daily distance goals, strategic locations for crossings, and scenic spots we didn’t want to miss, such as beautiful sandy beaches. We carefully selected sites for reliable water sources by validating BCMT notes about water sources against streams shown on CHS charts to ensure we wouldn’t encounter any surprises in July.

Tides, Currents, and Weather

We needed to be aware of tides and currents along our route. I summarized daily tide times from relevant tide stations on a compact 6”x6” paper, which I tucked into my chart case. We also noted sunrise and sunset times, as well as the date of the full moon during our trip. Spring tide would fall in the middle of our trip.

Currents that needed attention were identified. AyeTides App was helpful for this, while CHS marine charts showed very few current notations. The most critical current appeared to be crossing Slingsby Channel (no current marker on the CHS chart, but found through AyeTides map). Further inland from this channel flows the world’s strongest current, the Nakwakto Rapids, that has been measured at speeds up to 18 knots. We planned to closely monitor the Slingsby Channel current on the day of our crossing, as we could easily encounter currents of up to 8 knots if we were unprepared. We also identified there would be current in the final big crossing of the Queen Charlotte Strait.

For weather forecasts, we would rely on VHF (although not always reliable for getting reception) and InReach for updates. We familiarized ourselves with the light stations, land stations, buoys, and marine weather regions for when we’d be listening on the VHF weather station.

Gear

A comprehensive gear list was created by Jenna with assignments of personal vs. team gear and who would bring what. In-depth team discussions about gear focused on safety gear and essentials. A month before launch day, Eric and I did a six-day kayak trip in Deer Group to confirm all of our gear was in working order.

- Three first aid kits covering trauma to minor scrapes and aches. Planning for first aid items was extremely comprehensive as we would rely on our team for any medical issue since help was very far away. Two team members have wilderness first aid, one with combat first aid.

- Review of all repair kits and tools for patching large and small holes in kayaks, managing broken/lost hatch covers, spare rudder, gasket repair, foot pedal repair, you name it!

- For kayaking safety, we planned on a 50 foot tow belt and helmet per person (plus all standard safety gear requirements including drysuits).

- Predator safety equipment: after debating, we decided on bear bangers, alarm fencing, bear sprays and a 120 dB air horn.

- Critical redundancies identified: stoves and water filter systems. Plus purification tablets.

- Communication gear: VHF per person, and one InReach. One VHF has DSC, two VHFs can be recharged via USB.

- Flares: both close distance and long/launchable.

- Water: capacity for 3 days per person to be carried.

- Device charging: Two portable solar panels, several battery banks.

Food Preparation

We opted for individual meal plans rather than group sharing, with dehydrated food being the primary lunch and dinner source for Eric and me. Throughout the winter and spring, my dehydrator worked overtime, producing shepherd’s pie, chili, Thai curry, hummus, apples, and other recipes. Our meal planning focused on high-calorie, high-protein options.

Dehydrating our meals offers several advantages: it takes less space than fresh food, allows for control of ingredients (no salt or chemicals added, choice of our own plant-based proteins), and is more economical than purchasing pre-prepared dehydrated options. Additionally, preparing meals in camp would be straightforward, making mealtime a breeze.

Navigation

Paper charts and deck compasses would be our main navigation method. CHS charts were procured and I marked all locations of tent sites & water sources, bearings for crossing, distances between key segments, etc. I also highlighted any relevant points such as navigation markers and current arrows. Our back up navigation plan would be Navionics with tent sites uploaded.

Since BC Marine Trails is interested in assessing potential sites in the Central Coast, I was eager to help. I received a list of all the potential sites (coordinates) from BCMT, loaded them into Google Earth, identified those closest to our desired route, and marked them on the CHS charts as potential places to stop for breaks and assess.

Fitness

Recognizing that none of us were in our twenties anymore, fitness became an essential component of our preparation. Eric and I dedicated several days each week to paddling over the course of three to four months leading up to the trip, complemented by a six-day trip in the Deer Group to paddle fully loaded kayaks for training. I also incorporated a daily strength program to enhance my upper body endurance.

Kayak Considerations

Given that Eric and I would be using smaller kayaks for this two-week expedition, kayak capacity was a concern. My kayak had a capacity of 160 liters, while Eric’s new kayak, which was supposed to arrive in time, had a capacity of 200 liters. It became clear that the new kayak wouldn’t arrive in time, leading him to borrow a 175 liter kayak. This meant careful planning and gear selection were paramount. Jenna and Pat, with their larger kayaks, agreed to carry the bulk of team gear.

Packing Strategy

Compression dry bags became essential tools in our packing strategy. Eric and I invested in several for our tent, sleeping bags, and clothing, while utilizing standard nylon dry bags for everything else, limiting their size to 10-12 L to facilitate squeezing them into tight spaces.

I colour-coded my food bags by meal type for easy identification—yellow for breakfast, red for lunch, and blue for dinner.

A few days before our departure, we conducted a test pack, gathering all our gear to determine the best arrangement in our kayaks. This practice not only alleviated any worries about fitting in our supplies, but also helped us memorize the packing sequence for the actual trip.

Emergency Planning

Finally, our emergency planning was comprehensive. We compiled a list of emergency contacts, including water taxis, float planes, fishing lodges, hospitals, and marinas along our route in case of evacuation.

A float plan detailing our route options, expected arrival times at tent sites, and essential safety equipment was entrusted to a designated person responsible for alerting authorities should we fail to check in by a predetermined time.

Conclusion

The meticulous planning that went into our Central Coast paddling adventure was a testament to our commitment to safety and preparedness. From logistics and route planning to gear selection and meal preparation, every detail was carefully considered to ensure a successful expedition.

Resources

Examples of blogs about the route:

Valuable tools on the BCMT web site (for Members only):

To download tent sites in CSV format, visit the BCMT data table, select a paddling area, and export/save a CSV file to your computer.

To upload the tent sites (from above) to Google Earth, read these instructions on the BCMT website.

To measure distances between tent sites, use the Trip Planning icon on the Member Map.